I’ve read all of Kate Mosse’s fiction (with the exception of Eskimo Kissing). I borrowed Crucifix Lane from the library years ago, yet didn’t put two and two together when I was hooked by the blurb of Labyrinth. It was only when I was describing Crucifix Lane to someone, desperately trying to remember its author and title, that I did a web search for its plot points – and discovered the book I was remembering was by Kate Mosse (and yes, I’ve learnt my lesson and now write down everything I read!).

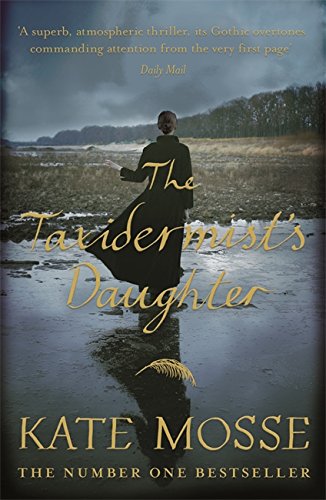

And because I’ve read all of them and loved every one, naturally her latest novel, The Taxidermist’s Daughter, was at the top of my Christmas list.

The Taxidermist’s Daughter is not a timeslip novel; it is set in the village of Fishbourne in Surrey, in 1812. Its story is not told by any of the characters involved in the event that is central to the book.

And yet... it kind of is a timeslip novel. The chief narrator, Connie, does slip through time now and then; but rather than slipping into the life of a person in the past, as she might do if she were a character in Kate’s Languedoc Trilogy, she slips into her own past – a past she can barely remember.

Because Connie had an accident that nobody will talk about. Connie has no idea why she calls her father by his surname. Connie doesn’t know why she remembers a yellow ribbon she doesn’t own, tied around hair that is not hers – or why she has a vague impression that she was once loved and cared for by someone who was not her mother but is, like her mother, no longer present in her life.

She also doesn’t understand why her father is tormented and retreats into the bottle, and why he gathers with other men in the graveyard at night. Why is she being watched, and is the dead girl washed up near the bottom of her garden just a coincidence? What surely can’t be a coincidence is that when her father goes missing, Dr.Woolston, the father of her new friend Harry, goes missing too – after signing an erroneous death certificate for the dead girl in Connie’s garden.

It’s this loss of memory and bewilderment at the strange events taking place in the present that make Connie the perfect narrator of the story. We begin to put the pieces together as Connie does, although we have the advantage of brief, enigmatic glimpses into the lives of other characters that help us begin to guess at the truth before she does.

The Taxidermist’s Daughter is a story of guilt, revenge, loyalty, love, loss and long-kept secrets. From the start, it reminded me of a Dickens novel; the vividly depicted marches and graveyard, the revelation of an old secret, people not being where or whom we expect them to be, and the names of characters and places that resonate so strongly with their role in the story. Could Crowther have had any other name, as he watches and waits for his moment? Could Blackthorn House have been called anything else? I think not. Connie’s father certainly has a metaphorical thorn in his side and yet, like Connie, we spend our time hoping, as the layers are pulled back and we get closer to the kernel of truth, that we’re being misdirected and her father is innocent of any wrongdoing.

In an interview in the Guardian in 2014, Mosse said she no longer wrote literary fiction: “I realised that I should have listened to myself sooner. My skill is storytelling, not literary fiction.”

Much as I hate to disagree with someone whose work I admire so much, I think she’s wrong. I’m not keen on the literary distinction anyway, but it’s possible to tell a great story while using beautiful and well-crafted language to do so. I know this because Kate does it so well – and she has done it again with this novel. The gothic, foreboding tone is set right from the start by her opening paragraph:

Midnight. in the graveyard of the church of St Peter and St Mary, men gather in silence on the edge of the drowned marshes.

Watching. Waiting.

Her blending of description with narrative is masterful, too, setting the scene simply and vividly:

The rain strikes the black umbrellas and cloth caps of the farm workers and dairymen and blacksmiths. Dripping down between neck and collar, skin and cloth. No one speaks.

Literary devices? Hmm, I’d say she can use a few. I’ll let you pick out the assortment contained in just this paragraph – and we’re still only on the first page:

It is a custom that has long since fallen away in most parts of Sussex, but not here. Not here, where the saltwater estuary flows put to the sea. Not here, in the shadow of the Old Salt Mill and the burnt-out remains of Farhill’s Mill, its rotting timbers revealed at low tide. Here, the old superstitions still hold sway.

The drama of the final scenes, the wildness of the weather, the isolation of the village and Blackthorn House, and the bittersweet twist when the truth is revealed, make this an atmospheric and compelling gothic thriller – and a perfect example of a book where plot, characterisation, theme and setting are perfectly balanced and beautifully blended. I won’t say effortlessly blended, because this kind of excellence requires a great deal of effort – effort that, thankfully, Kate Mosse seems willing and very capable of putting in.

Fabulous! 9/10